Typically, when I review a player’s case for their Hall of Fame candidacy, it is done prior to their induction. However, when Harold Baines was inducted, there was such a fervor I felt compelled to review the candidacy of an actual Hall of Famer. The strange part about the reaction has been the slings and arrows of outrageous fortune toward the man himself. Make no mistake, Harold Baines didn’t select himself. Harold Baines didn’t plead his case or campaign for selection. One day he was minding his own business enjoying his well-deserved retirement and the next day he was swept up into a whirlwind of the Hall of Fame.

1.Quiet

2.Strong Postseason Record

3.38.8 WAR

4.Two Time Edgar Martinez Award Winner

5.#3

6.1,628 RBIs

7.2,866 Hits

8.Six time All-Star

9.MVP voting

10.Top 5 DH of All-Time

11.Black Ink – 3, Gray Ink – 40, Hall of Fame Monitor – 67, Hall of Fame Standards – 44

12.Uniqueness

13.4,604 Total Bases

14.121 OPS+

1. Quiet - Most Hall of Famers have a famous story that has nothing to do with statistics or Hall of Fame worthiness. These can be something remarkable like Babe Ruth’s called shot and Willie Mays’ “The Catch”, or these can be crazy like Robin Ventura getting 5 hits off of Nolan Ryan and George Brett’s Pine Tar Incident, or these can simply just be a memorable quote like Lou Gehrig’s “I am the luckiest man on the face of the earth” and Rickey Henderson’s “Today I am the greatest of all-time”. And that’s the thing about Harold Baines, he was quiet. Baines played 22 years without pomp, without controversy, without a clever quip, and without flash. He was perhaps the quietest 20+ year veteran who ever played the game. He showed up, did his job, and went home. In fact, the most interesting story about Baines happened to him 9 years before he saw his first Major League pitch. Hall of Fame owner, Bill Veeck saw Baines play as a Little Leaguer when Baines was 12 and followed his career until 1977 when Veeck’s White Sox drafted Baines #1 overall. In a way, Baines’ lack of story makes him stand out as a somewhat unique Hall of Famer. It’s possible his lack of story is one of the reasons there may have been such a harsh response to his induction.

2. Strong Postseason Record – None of Harold Baines’ teams won the World Series. But they did make the Postseason six times with one World Series appearance. In his sole World Series appearance, Baines only hit .143 but it was the 1990 Series and being the A’s DH, he only got 8 at bats since they were swept. However, Baines was great when the spotlight was on his team. His career Postseason slash line is .324/.378/.510 hitting over .350 in five of his eight Postseason series. While he gets dinged for the 1990 World Series, the overall body of work looks good next to most Hall of Famers.

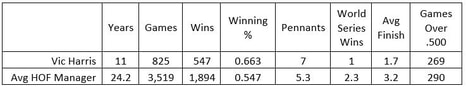

3. 38.8 WAR – 38.8 WAR is a low total for a Hall of Famer. Excluding pitchers, among Hall of Fame players with at least 3,000 Plate Appearances there are 19 players with a lower WAR total than Harold Baines. Four of the 19 are Negro Leaguers. Two of the 19 are 19th Century Baseball players. The remaining 13 were elected for one (or more) of three reasons: 1. Reputation, 2. Association, 3. A Singular Accomplishment. Reputation: Rick Ferrell was considered one of the best catchers of his era and had the added benefit of being an executive with the Tigers during their two World Championships. At the time of his selection, Ray Schalk was considered one of the great defensive catchers of his time. He was also one of the few 1919 White Sox players who played to win. George Kell was generally regarded as one of the great 3rd basemen of his era and made 10 All-Star appearances, but he also spent 37 years after his career as a successful broadcaster for the Tigers. Pie Traynor was often cited as the greatest 3rd baseman of his era. Association: High Pockets Kelly was elected by the “Friends of Frisch” Veterans Committee. Kelly specifically was the “finest first baseman” Frisch had ever seen. Freddie Lindstrom was also selected by the Frisch/Terry Committee. Chick Hafey was also selected by the Frisch/Terry Committee; though his induction was defended using the Koufax argument, Hafey’s brilliance in his short, injury marred career pales in comparison to Koufax. Ross Youngs was also selected by the Frisch Committee, though he died tragically young. As was Jim Bottomley. Lloyd Waner was the brother of well qualified Hall of Famer Paul Waner. Ernie Lombardi was finally selected by the Veterans Committee once his friend and contemporary Birdie Tebbetts was added to the committee. Singular Accomplishment: Bill Mazeroski is often cited as the greatest defensive 2nd baseman of all-time but he also is given credit for his Walk-Off HR to end game 7 of the 1960 World Series. Hack Wilson still holds the record for most RBIs in a single season. Of these 3 options, Baines falls into the Association category as his candidacy was advocated (and defended) by Veterans Committee members, Tony LaRussa and Jerry Reinsdorf. Of the three categories, Association is the weakest. Coupled with his WAR total, this is probably the weakest point of Baines’ case. Even looking at the players just above him, Campy, Bresnahan, and Rizzuto, and two of these are weak selections. Bresnahan can probably be pointed to as a line of demarcation in the Hall of Fame when the standards of the Hall softened. Campanella is probably the first on the list to show a well-qualified Hall of Famer. And Scooter was, well, a popular broadcaster who had friends on the committee. Baines’ issue is, it had been almost 20 years since one of the players listed above got this treatment, (Maz) and he last played in 1972.

4. Two Time Edgar Martinez Award Winner – I find it humorous that Baines having been named DH of the year in 1987 and 1988 is now recognized as having won an award named for a player who was a Rookie the first time Baines won the award. It is interesting to note there are now seven Hall of Famers who have won this award. He is also one of 10 to have won the award multiple times. As Hall of Fame DHs are a relatively new phenomenon, it is probably too early to attribute any correlation to this particular award. However, one of the criteria often asked when considering a player’s Hall of Fame worthiness is, did this player dominate his league or his position in his era? Well, his two Edgar Awards were back to back, and he probably should have won the award again in 1989 and 1990 but was traded during both seasons which can always muddy awards. Plus, he didn’t play great for Texas after the 1989 trade. In 1991, Chili Davis had an outstanding season for the Champion Twins, but Baines was probably the 2nd best DH that season. It is safe to say, over Baines’ first 5 seasons as a DH, he was the best DH in the game.

5. #3 – Baines wore #3 most of his career. Normally this wouldn’t be worth noting. However, the Chicago White Sox thought so much of Harold Baines that they retired his number. Again, you may be thinking, “so what? A lot of players have their number retired.” Well, Baines is one of seven to have had his number retired…while still active! The others include Hall of Famers, Robin Roberts, Frank Robinson, Willie Mays, Harmon Killebrew, Phil Niekro, Nolan Ryan. (I’m excluding players who had their number retired in the final month of their career, like Bob Gibson, Lou Brock, and Ozzie Smith. Apparently, the Cardinals like to retire numbers right before a player says goodbye)

In reviewing the 212 times a player or manager have had their number retired by a team, 75% of those are recognizing a Hall of Fame player. (86% of them are recognizing a player who is either in the Hall, clearly going to be soon, or has at least had multiple showings on a Veterans Committee ballot). While having your number retired doesn’t mean you are a Hall of Famer, it is clearly a level of recognition that few receive and those who have received it are generally all-time great players.

When a player or manager has their number retired, it is an honor reserved for recognizing a person’s impact to a franchise. It isn’t necessarily indicative of a Hall of Fame career. In fact, it stands to reason players sometimes get their number retired because they made the Hall of Fame and not the other way around. But in the case of Harold Baines, the White Sox thought him important enough to their franchise to make him just the 6th player to have his number retired while still active. As it relates to his case, this is essentially an award he received as a player – a very rare award, and therefore strengthens his case.

6. 1,628 RBIs – In the Sabermetric Era, certain stats have been identified as having been overvalued in the past. Among those are RBIs. While it is fair to say RBIs are not as important as other stats when determining the overall value of a player’s career, it is not to say they are without value. However, we sometimes become so dismissive of a statistic, we treat it as if it is without value. This has happened with the RBI metric. I think the issue is RBIs are an output stat. They are an indication of other positive activities and therefore measuring them can be duplicitous when determining a player’s value. For example, a batter doesn’t hit an RBI. They hit a single or a double which may lead to an RBI. A player who has a lot of RBIs did a lot of positive activities. For Harold Baines, his 1,628 RBIs were good for 21st All-Time when he retired in 2001. The 20 players above him are all Hall of Famers. In fact, the 19 players below him are all Hall of Famers except for Barry Bonds. As Bonds (and Ripken) was not yet HOF eligible at the time of Baines’ retirement, every eligible player in the top 40 of RBIs at the time was enshrined. There simply was no precedent for keeping a player out of the Hall of Fame with that many Runs Batted In.

7. 2,866 Hits – Not exactly the 3,000 Hit Club. But the 2,800 Club is strongly represented in Cooperstown. At the time of his retirement, every eligible player with 2,800 hits was inducted. Baines was 37th on this list and he just squeaked above 2,800 Hits. If we go to 2,600 Hits, the list gets a little shakier. At the time of his retirement, 84% of the eligible players with 2,600 Hits were Hall of Famers. His hit total is definitely a strong part of his argument. Sometimes people will argue that had there been no player strikes, Baines would have made the 3,000 hit club. Reviewing his 1981, 1994, and 1995 seasons and projecting his Hits over the games he was on pace to play as well as using his batting average in those seasons to extrapolate his “missing hits” (which is probably the most optimistic approach one could take), he projects to a career total of 2,974. While it is reasonable to expect the White Sox would have let him keep swinging for those last 26 Hits, Baines was hurt in his final season and when he did play he was pretty awful. Regardless, his career hit total of 2,866 remains impressive. It’s definitely “Hall of Famesque”.

8. Six time All-Star - This isn’t a particularly remarkable number. There have been 259 players to make six or more All-Star teams. These range from obvious HOFers like Willie McCovey and Billy Williams to not in a million years would they ever make the Hall of Fame like Eddie Miller and Del Crandall. For what it’s worth, among DHs, only Ortiz, Cruz, and Edgar made more All-Star appearances. Being a six time All-Star neither helps nor hurts Baines’ case.

9. MVP voting – Everyone looks at Baines and thinks of his time as a slow, plodding DH. But before his knees gave out, he was considered a great outfield prospect with a good arm. Drafted #1 overall, he made his mark pretty early in his MLB career. His White Sox, led by Carlton Fisk, took the AL West crown in 1983 and Baines finished #10 in the MVP voting. Overall, Baines had 2 top 10 finishes and 2 other top 20 finishes. Once he moved to DH, well DHs don’t win MVPs. Molitor, Thomas, and Ortiz all came closest with 2nd place finishes. And technically, Ohtani just won an MVP playing mostly DH, but he was also doing something else incredible. As far as MVP voting is concerned, Baines is unremarkable.

10. Top 5 DH of All-Time – There is an argument to be made regarding the validity of treating “DH” as its own independent position. The position was created as an AL-Only position in 1973. The first player to be inducted into the Hall of Fame while playing more of his games as a DH than any other position, was Paul Molitor in 2004. Frank Thomas was the next HOFer inducted having played slightly more games at DH than 1st Base. However, the Hall of Fame does not recognize Molitor or Thomas as DHs. Molitor played several positions well and the Hall regards him as a 3rd baseman. Frank Thomas cemented his Hall of Fame credentials as a 1st baseman. Parceling out the DH as its own position, there are just 3 recognized HOF DHs: Edgar Martinez, David Ortiz, and Harold Baines. With 3 inductees, it is the least represented position in the Hall; which makes sense since it only has a 50-year history with almost all of that coming from one league. Regardless, it is fair to rank Baines as 3rd best between Edgar, Ortiz, and Baines.

So, how many DHs should we expect in the Hall at this point? Well, if the DH is 50 years old and almost all of that is in one league, there’s really the equivalent of 25 full seasons worth of DHing (really 22 years worth as 2017 is the most recent year of HOF eligibility). Baseball is ~150ish years old. There is an average of around 22 HOFers at each position (excluding pitchers, of course). That’s one Hall of Famer at each position every 6 years or so depending on how you want to count the years. With 22 full seasons worth of DHing, we could expect there to be 3-4 DHs in the Hall.

If Harold Baines is one of the 3-4 best DHs ever, it would be reasonable to expect him to be in the Hall of Fame. According to WAR, the ranking goes: 1. Edgar (68.4), 2. Ortiz (55.3), 3. Nelson Cruz (42.5), 4. Harold Baines (38.8), 5. Don Baylor (28.5). According to Win Shares it’s: 1. Ortiz (316), 2. Baines (307), 3. Edgar (305), 4. Cruz (266), 5. Baylor (262). Baines has the most Hits of any DH ever, 2nd most runs scored, 3rd most HRs, 2nd most RBIs, and the 7th best OPS+. It is reasonable to rank Harold Baines as the 3rd or 4th best DH of all-time.

11. Black Ink – 3, Gray Ink – 40, Hall of Fame Monitor – 67, Hall of Fame Standards – 44 - On a relative scale, Baines performs best on the Hall of Fame Standards metric; probably because he played a long time and accumulated a lot of stats. He did lead the league in slugging once and had a few top 10 finishes here and there. Overall, these metrics do not help his case.

12. Uniqueness – In Bill James’ “The Politics of Glory,” he outlines a system of comparing the sum total of a player’s career with another to determine how similar they are. Not to “eat the bones” but the system is a great way to answer the question, does this player’s career resemble anyone else’s in history? Often, a Hall of Famer represents a player who has had a career unlike any other and that uniqueness can distinguish the player as Hall of Fame worthy. Sometimes their uniqueness can also work against them as perhaps the voters don’t know how to handle something they’ve never seen or tried to measure. But if a player is most similar to a bunch of Hall of Famers, that could also indicate a player may be worthy of inclusion. Harold Baines was fairly unique. The most similar player to Baines is a Hall of Famer, Tony Perez, with a similarity score of 944. The next nine most similar players to Baines all come in below 900 and among his 10 most similar players, four are Hall of Famers who were inducted by the BBWAA – Perez, Al Kaline, Billy Williams, and Andre Dawson. Three others have decent Hall of Fame cases in their own right (Dwight Evans, Dave Parker, and Carlos Beltran).

13. 4,604 Total Bases – At the time of his retirement, Harold was 28th All-Time in Total Bases. Again, every player above him who was eligible at the time, was in the Hall of Fame. And in the top 40, all except Dave Parker are enshrined.

14. 121 OPS+ - Harold Baines has a career OPS+ of 121. That is better than about a third of the Hall of Fame. Of course, some Hall of Famers are in because they were a light hitting middle infielder with a dazzling glove (Luis Aparicio) or were considered an integral part of a legendary team (Pee Wee Reese) or both (Bill Mazeroski). And there are several Hall of Famers with a lesser OPS+ than Baines who are generally considered Hall of Famers with strong offensive reputations like Carlton Fisk, Cal Ripken, and Andre Dawson. Of course, a 121 OPS+ doesn’t get you in the Hall of Fame. But a 121 OPS+ is the kind of OPS+ that holds its own against other HOFers. In Baines’ case, a more distinguished accomplishment is that he had 19 consecutive seasons of an OPS+ above 100. At the time of his retirement, only 13 other players had posted more than 19 consecutive OPS+ seasons above 100: Cap Anson, Eddie Collins, Ty Cobb, Hank Aaron, Stan Musial, Joe Morgan, Frank Robinson, Willie Mays, Babe Ruth, Tony Gwynn, Dave Winfield, Mule Suttles, and Jim O’Rourke. Ted Williams and Tris Speaker also posted 19 consecutive seasons. This displays the type of consistency we would only expect from a Hall of Famer. Forget consecutive. If we simply look at the 51 players with the most OPS+ seasons above 100, here are the only players not in the Hall of Fame: Barry Bonds, Alex Rodriguez, Rafael Palmeiro, Gary Sheffield, Darrell Evans, and Rusty Staub. As it relates to his case, Baines’ OPS+ accomplishments aren’t Ruthian. However, they are Hendersonian, Dawsonian, and maybe a little Winfieldian.

I’ve written this previously, there are 3 typical paths to the Hall: Longevity, Peak Value, and Dominance. Harold Baines was not a dominant force in his prime. But Baines’ case really isn’t predicated on being a perennial league leader; it’s predicated on being someone who accumulated Hall of Fame totals and someone who was the best at his position for a period of time. Harold Baines didn’t put up a lot of “Hall of Fame-looking” individual seasons. He never had a 30 HR season; but he did have 11 seasons with 20 or more HRs. His lifetime batting average isn’t .300, but he did hit .300+ eight times and .290+ five times. He never led the league in OBP, but he did post a .350+ OBP 12 times. From beginning to end, Harold Baines was consistent. He really didn’t have a decline phase other than playing time. In fact, he was a little better in his second half than he was in his first half. In the first half of his career, he slashed .288/.344/.461 while in the second half he slashed .291/.371/.471. He hit a homerun every 28 at bats in the first half of his career and hit one every 23 in the second half.

It would seem part of the argument for Harold Baines may be the nebulous “…integrity, sportsmanship, character, and contributions to the team(s) on which the player played” clause. But Harold Baines was also a consistent hitter who excelled in the post-season. He accumulated near-Hall of Fame career totals and definitely has some statistical achievements that stand up to most Hall of Famers. I don’t think it unreasonable that Harold Baines is in the Hall of Fame. There are others with less impressive careers, and his numbers really aren’t that far away from being a slam dunk Hall of Famer. Another 134 Hits and there would be little debate. He was probably the best DH in the game for half of a decade. There is an argument for him being the 3rd greatest at his position ever and the HOF DH will come more into focus over the next couple of decades. The first three 3rd basemen inducted were: Jimmy Collins, Homerun Baker, and Pie Traynor. It’s reasonable that Baines may simply be the Pie Traynor of the DH position.

He certainly doesn’t deserve the vitriol he’s received since his enshrinement. Harold Baines was a professional hitter who carried himself like Teddy Roosevelt, walking softly and carrying a big stick. He was asked to just hit and he did it better than nearly anyone ever at his position.

1.Quiet

2.Strong Postseason Record

3.38.8 WAR

4.Two Time Edgar Martinez Award Winner

5.#3

6.1,628 RBIs

7.2,866 Hits

8.Six time All-Star

9.MVP voting

10.Top 5 DH of All-Time

11.Black Ink – 3, Gray Ink – 40, Hall of Fame Monitor – 67, Hall of Fame Standards – 44

12.Uniqueness

13.4,604 Total Bases

14.121 OPS+

1. Quiet - Most Hall of Famers have a famous story that has nothing to do with statistics or Hall of Fame worthiness. These can be something remarkable like Babe Ruth’s called shot and Willie Mays’ “The Catch”, or these can be crazy like Robin Ventura getting 5 hits off of Nolan Ryan and George Brett’s Pine Tar Incident, or these can simply just be a memorable quote like Lou Gehrig’s “I am the luckiest man on the face of the earth” and Rickey Henderson’s “Today I am the greatest of all-time”. And that’s the thing about Harold Baines, he was quiet. Baines played 22 years without pomp, without controversy, without a clever quip, and without flash. He was perhaps the quietest 20+ year veteran who ever played the game. He showed up, did his job, and went home. In fact, the most interesting story about Baines happened to him 9 years before he saw his first Major League pitch. Hall of Fame owner, Bill Veeck saw Baines play as a Little Leaguer when Baines was 12 and followed his career until 1977 when Veeck’s White Sox drafted Baines #1 overall. In a way, Baines’ lack of story makes him stand out as a somewhat unique Hall of Famer. It’s possible his lack of story is one of the reasons there may have been such a harsh response to his induction.

2. Strong Postseason Record – None of Harold Baines’ teams won the World Series. But they did make the Postseason six times with one World Series appearance. In his sole World Series appearance, Baines only hit .143 but it was the 1990 Series and being the A’s DH, he only got 8 at bats since they were swept. However, Baines was great when the spotlight was on his team. His career Postseason slash line is .324/.378/.510 hitting over .350 in five of his eight Postseason series. While he gets dinged for the 1990 World Series, the overall body of work looks good next to most Hall of Famers.

3. 38.8 WAR – 38.8 WAR is a low total for a Hall of Famer. Excluding pitchers, among Hall of Fame players with at least 3,000 Plate Appearances there are 19 players with a lower WAR total than Harold Baines. Four of the 19 are Negro Leaguers. Two of the 19 are 19th Century Baseball players. The remaining 13 were elected for one (or more) of three reasons: 1. Reputation, 2. Association, 3. A Singular Accomplishment. Reputation: Rick Ferrell was considered one of the best catchers of his era and had the added benefit of being an executive with the Tigers during their two World Championships. At the time of his selection, Ray Schalk was considered one of the great defensive catchers of his time. He was also one of the few 1919 White Sox players who played to win. George Kell was generally regarded as one of the great 3rd basemen of his era and made 10 All-Star appearances, but he also spent 37 years after his career as a successful broadcaster for the Tigers. Pie Traynor was often cited as the greatest 3rd baseman of his era. Association: High Pockets Kelly was elected by the “Friends of Frisch” Veterans Committee. Kelly specifically was the “finest first baseman” Frisch had ever seen. Freddie Lindstrom was also selected by the Frisch/Terry Committee. Chick Hafey was also selected by the Frisch/Terry Committee; though his induction was defended using the Koufax argument, Hafey’s brilliance in his short, injury marred career pales in comparison to Koufax. Ross Youngs was also selected by the Frisch Committee, though he died tragically young. As was Jim Bottomley. Lloyd Waner was the brother of well qualified Hall of Famer Paul Waner. Ernie Lombardi was finally selected by the Veterans Committee once his friend and contemporary Birdie Tebbetts was added to the committee. Singular Accomplishment: Bill Mazeroski is often cited as the greatest defensive 2nd baseman of all-time but he also is given credit for his Walk-Off HR to end game 7 of the 1960 World Series. Hack Wilson still holds the record for most RBIs in a single season. Of these 3 options, Baines falls into the Association category as his candidacy was advocated (and defended) by Veterans Committee members, Tony LaRussa and Jerry Reinsdorf. Of the three categories, Association is the weakest. Coupled with his WAR total, this is probably the weakest point of Baines’ case. Even looking at the players just above him, Campy, Bresnahan, and Rizzuto, and two of these are weak selections. Bresnahan can probably be pointed to as a line of demarcation in the Hall of Fame when the standards of the Hall softened. Campanella is probably the first on the list to show a well-qualified Hall of Famer. And Scooter was, well, a popular broadcaster who had friends on the committee. Baines’ issue is, it had been almost 20 years since one of the players listed above got this treatment, (Maz) and he last played in 1972.

4. Two Time Edgar Martinez Award Winner – I find it humorous that Baines having been named DH of the year in 1987 and 1988 is now recognized as having won an award named for a player who was a Rookie the first time Baines won the award. It is interesting to note there are now seven Hall of Famers who have won this award. He is also one of 10 to have won the award multiple times. As Hall of Fame DHs are a relatively new phenomenon, it is probably too early to attribute any correlation to this particular award. However, one of the criteria often asked when considering a player’s Hall of Fame worthiness is, did this player dominate his league or his position in his era? Well, his two Edgar Awards were back to back, and he probably should have won the award again in 1989 and 1990 but was traded during both seasons which can always muddy awards. Plus, he didn’t play great for Texas after the 1989 trade. In 1991, Chili Davis had an outstanding season for the Champion Twins, but Baines was probably the 2nd best DH that season. It is safe to say, over Baines’ first 5 seasons as a DH, he was the best DH in the game.

5. #3 – Baines wore #3 most of his career. Normally this wouldn’t be worth noting. However, the Chicago White Sox thought so much of Harold Baines that they retired his number. Again, you may be thinking, “so what? A lot of players have their number retired.” Well, Baines is one of seven to have had his number retired…while still active! The others include Hall of Famers, Robin Roberts, Frank Robinson, Willie Mays, Harmon Killebrew, Phil Niekro, Nolan Ryan. (I’m excluding players who had their number retired in the final month of their career, like Bob Gibson, Lou Brock, and Ozzie Smith. Apparently, the Cardinals like to retire numbers right before a player says goodbye)

In reviewing the 212 times a player or manager have had their number retired by a team, 75% of those are recognizing a Hall of Fame player. (86% of them are recognizing a player who is either in the Hall, clearly going to be soon, or has at least had multiple showings on a Veterans Committee ballot). While having your number retired doesn’t mean you are a Hall of Famer, it is clearly a level of recognition that few receive and those who have received it are generally all-time great players.

When a player or manager has their number retired, it is an honor reserved for recognizing a person’s impact to a franchise. It isn’t necessarily indicative of a Hall of Fame career. In fact, it stands to reason players sometimes get their number retired because they made the Hall of Fame and not the other way around. But in the case of Harold Baines, the White Sox thought him important enough to their franchise to make him just the 6th player to have his number retired while still active. As it relates to his case, this is essentially an award he received as a player – a very rare award, and therefore strengthens his case.

6. 1,628 RBIs – In the Sabermetric Era, certain stats have been identified as having been overvalued in the past. Among those are RBIs. While it is fair to say RBIs are not as important as other stats when determining the overall value of a player’s career, it is not to say they are without value. However, we sometimes become so dismissive of a statistic, we treat it as if it is without value. This has happened with the RBI metric. I think the issue is RBIs are an output stat. They are an indication of other positive activities and therefore measuring them can be duplicitous when determining a player’s value. For example, a batter doesn’t hit an RBI. They hit a single or a double which may lead to an RBI. A player who has a lot of RBIs did a lot of positive activities. For Harold Baines, his 1,628 RBIs were good for 21st All-Time when he retired in 2001. The 20 players above him are all Hall of Famers. In fact, the 19 players below him are all Hall of Famers except for Barry Bonds. As Bonds (and Ripken) was not yet HOF eligible at the time of Baines’ retirement, every eligible player in the top 40 of RBIs at the time was enshrined. There simply was no precedent for keeping a player out of the Hall of Fame with that many Runs Batted In.

7. 2,866 Hits – Not exactly the 3,000 Hit Club. But the 2,800 Club is strongly represented in Cooperstown. At the time of his retirement, every eligible player with 2,800 hits was inducted. Baines was 37th on this list and he just squeaked above 2,800 Hits. If we go to 2,600 Hits, the list gets a little shakier. At the time of his retirement, 84% of the eligible players with 2,600 Hits were Hall of Famers. His hit total is definitely a strong part of his argument. Sometimes people will argue that had there been no player strikes, Baines would have made the 3,000 hit club. Reviewing his 1981, 1994, and 1995 seasons and projecting his Hits over the games he was on pace to play as well as using his batting average in those seasons to extrapolate his “missing hits” (which is probably the most optimistic approach one could take), he projects to a career total of 2,974. While it is reasonable to expect the White Sox would have let him keep swinging for those last 26 Hits, Baines was hurt in his final season and when he did play he was pretty awful. Regardless, his career hit total of 2,866 remains impressive. It’s definitely “Hall of Famesque”.

8. Six time All-Star - This isn’t a particularly remarkable number. There have been 259 players to make six or more All-Star teams. These range from obvious HOFers like Willie McCovey and Billy Williams to not in a million years would they ever make the Hall of Fame like Eddie Miller and Del Crandall. For what it’s worth, among DHs, only Ortiz, Cruz, and Edgar made more All-Star appearances. Being a six time All-Star neither helps nor hurts Baines’ case.

9. MVP voting – Everyone looks at Baines and thinks of his time as a slow, plodding DH. But before his knees gave out, he was considered a great outfield prospect with a good arm. Drafted #1 overall, he made his mark pretty early in his MLB career. His White Sox, led by Carlton Fisk, took the AL West crown in 1983 and Baines finished #10 in the MVP voting. Overall, Baines had 2 top 10 finishes and 2 other top 20 finishes. Once he moved to DH, well DHs don’t win MVPs. Molitor, Thomas, and Ortiz all came closest with 2nd place finishes. And technically, Ohtani just won an MVP playing mostly DH, but he was also doing something else incredible. As far as MVP voting is concerned, Baines is unremarkable.

10. Top 5 DH of All-Time – There is an argument to be made regarding the validity of treating “DH” as its own independent position. The position was created as an AL-Only position in 1973. The first player to be inducted into the Hall of Fame while playing more of his games as a DH than any other position, was Paul Molitor in 2004. Frank Thomas was the next HOFer inducted having played slightly more games at DH than 1st Base. However, the Hall of Fame does not recognize Molitor or Thomas as DHs. Molitor played several positions well and the Hall regards him as a 3rd baseman. Frank Thomas cemented his Hall of Fame credentials as a 1st baseman. Parceling out the DH as its own position, there are just 3 recognized HOF DHs: Edgar Martinez, David Ortiz, and Harold Baines. With 3 inductees, it is the least represented position in the Hall; which makes sense since it only has a 50-year history with almost all of that coming from one league. Regardless, it is fair to rank Baines as 3rd best between Edgar, Ortiz, and Baines.

So, how many DHs should we expect in the Hall at this point? Well, if the DH is 50 years old and almost all of that is in one league, there’s really the equivalent of 25 full seasons worth of DHing (really 22 years worth as 2017 is the most recent year of HOF eligibility). Baseball is ~150ish years old. There is an average of around 22 HOFers at each position (excluding pitchers, of course). That’s one Hall of Famer at each position every 6 years or so depending on how you want to count the years. With 22 full seasons worth of DHing, we could expect there to be 3-4 DHs in the Hall.

If Harold Baines is one of the 3-4 best DHs ever, it would be reasonable to expect him to be in the Hall of Fame. According to WAR, the ranking goes: 1. Edgar (68.4), 2. Ortiz (55.3), 3. Nelson Cruz (42.5), 4. Harold Baines (38.8), 5. Don Baylor (28.5). According to Win Shares it’s: 1. Ortiz (316), 2. Baines (307), 3. Edgar (305), 4. Cruz (266), 5. Baylor (262). Baines has the most Hits of any DH ever, 2nd most runs scored, 3rd most HRs, 2nd most RBIs, and the 7th best OPS+. It is reasonable to rank Harold Baines as the 3rd or 4th best DH of all-time.

11. Black Ink – 3, Gray Ink – 40, Hall of Fame Monitor – 67, Hall of Fame Standards – 44 - On a relative scale, Baines performs best on the Hall of Fame Standards metric; probably because he played a long time and accumulated a lot of stats. He did lead the league in slugging once and had a few top 10 finishes here and there. Overall, these metrics do not help his case.

12. Uniqueness – In Bill James’ “The Politics of Glory,” he outlines a system of comparing the sum total of a player’s career with another to determine how similar they are. Not to “eat the bones” but the system is a great way to answer the question, does this player’s career resemble anyone else’s in history? Often, a Hall of Famer represents a player who has had a career unlike any other and that uniqueness can distinguish the player as Hall of Fame worthy. Sometimes their uniqueness can also work against them as perhaps the voters don’t know how to handle something they’ve never seen or tried to measure. But if a player is most similar to a bunch of Hall of Famers, that could also indicate a player may be worthy of inclusion. Harold Baines was fairly unique. The most similar player to Baines is a Hall of Famer, Tony Perez, with a similarity score of 944. The next nine most similar players to Baines all come in below 900 and among his 10 most similar players, four are Hall of Famers who were inducted by the BBWAA – Perez, Al Kaline, Billy Williams, and Andre Dawson. Three others have decent Hall of Fame cases in their own right (Dwight Evans, Dave Parker, and Carlos Beltran).

13. 4,604 Total Bases – At the time of his retirement, Harold was 28th All-Time in Total Bases. Again, every player above him who was eligible at the time, was in the Hall of Fame. And in the top 40, all except Dave Parker are enshrined.

14. 121 OPS+ - Harold Baines has a career OPS+ of 121. That is better than about a third of the Hall of Fame. Of course, some Hall of Famers are in because they were a light hitting middle infielder with a dazzling glove (Luis Aparicio) or were considered an integral part of a legendary team (Pee Wee Reese) or both (Bill Mazeroski). And there are several Hall of Famers with a lesser OPS+ than Baines who are generally considered Hall of Famers with strong offensive reputations like Carlton Fisk, Cal Ripken, and Andre Dawson. Of course, a 121 OPS+ doesn’t get you in the Hall of Fame. But a 121 OPS+ is the kind of OPS+ that holds its own against other HOFers. In Baines’ case, a more distinguished accomplishment is that he had 19 consecutive seasons of an OPS+ above 100. At the time of his retirement, only 13 other players had posted more than 19 consecutive OPS+ seasons above 100: Cap Anson, Eddie Collins, Ty Cobb, Hank Aaron, Stan Musial, Joe Morgan, Frank Robinson, Willie Mays, Babe Ruth, Tony Gwynn, Dave Winfield, Mule Suttles, and Jim O’Rourke. Ted Williams and Tris Speaker also posted 19 consecutive seasons. This displays the type of consistency we would only expect from a Hall of Famer. Forget consecutive. If we simply look at the 51 players with the most OPS+ seasons above 100, here are the only players not in the Hall of Fame: Barry Bonds, Alex Rodriguez, Rafael Palmeiro, Gary Sheffield, Darrell Evans, and Rusty Staub. As it relates to his case, Baines’ OPS+ accomplishments aren’t Ruthian. However, they are Hendersonian, Dawsonian, and maybe a little Winfieldian.

I’ve written this previously, there are 3 typical paths to the Hall: Longevity, Peak Value, and Dominance. Harold Baines was not a dominant force in his prime. But Baines’ case really isn’t predicated on being a perennial league leader; it’s predicated on being someone who accumulated Hall of Fame totals and someone who was the best at his position for a period of time. Harold Baines didn’t put up a lot of “Hall of Fame-looking” individual seasons. He never had a 30 HR season; but he did have 11 seasons with 20 or more HRs. His lifetime batting average isn’t .300, but he did hit .300+ eight times and .290+ five times. He never led the league in OBP, but he did post a .350+ OBP 12 times. From beginning to end, Harold Baines was consistent. He really didn’t have a decline phase other than playing time. In fact, he was a little better in his second half than he was in his first half. In the first half of his career, he slashed .288/.344/.461 while in the second half he slashed .291/.371/.471. He hit a homerun every 28 at bats in the first half of his career and hit one every 23 in the second half.

It would seem part of the argument for Harold Baines may be the nebulous “…integrity, sportsmanship, character, and contributions to the team(s) on which the player played” clause. But Harold Baines was also a consistent hitter who excelled in the post-season. He accumulated near-Hall of Fame career totals and definitely has some statistical achievements that stand up to most Hall of Famers. I don’t think it unreasonable that Harold Baines is in the Hall of Fame. There are others with less impressive careers, and his numbers really aren’t that far away from being a slam dunk Hall of Famer. Another 134 Hits and there would be little debate. He was probably the best DH in the game for half of a decade. There is an argument for him being the 3rd greatest at his position ever and the HOF DH will come more into focus over the next couple of decades. The first three 3rd basemen inducted were: Jimmy Collins, Homerun Baker, and Pie Traynor. It’s reasonable that Baines may simply be the Pie Traynor of the DH position.

He certainly doesn’t deserve the vitriol he’s received since his enshrinement. Harold Baines was a professional hitter who carried himself like Teddy Roosevelt, walking softly and carrying a big stick. He was asked to just hit and he did it better than nearly anyone ever at his position.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed